Welcome to Science Goddess. That’s me! I’m a science writer and this Substack is a place for me to rave about science in the two-fold meaning of this term. I’ll be talking about things I love in science, or what I call its ‘conceptual enchantments’ – quasicrystals, quantum mechanics, the geometry of coral reefs, and so forth. I’ll also write about dimensions of the scientific enterprise that are darker and which I feel need public airing, particularly issues relating to the social practice of science and the impacts of STEM in our lives. In addition to writing, I also do projects at the intersection of science and art, and from time to time I’ll post about this nexus too. First up I want to address the question “Who is science writing for?”

POST #1: WHO IS SCIENCE WRITING FOR?

“It is a truth universally acknowledged” that writing about science for the public is a good thing. But what kind of a ‘good’ is it? And who is this ‘public’ we science enthusiasts so frequently invoke? [i]

Science writing is first and foremost an act of communication. We aim to communicate the wonders, discoveries, and pitfalls of science to those not already in the know. In science writing circles there is a lot of discussion about how we communicators can do a better job. But communication is a bi-valent word: for anything to be communicated, there has to be both a transmitter and a receiver. Without good reception nothing gets communicated, no matter how good the transmitter may be.

In my thirty-plus years as a science writer I’ve sat through endless meetings about how we can be better transmitters of scientific findings. I’ve rarely heard a discussion – unless I initiated it – about how things are going on the receiving end. Who are ‘the people’ we’re supposedly transmitting to, and what are their needs?

This question has been at the heart of my work since the 1980’s when, after completing degrees in physics and mathematics, I decided to become a science writer instead of going to grad school.[ii] My first job was one I created for myself: I convinced an Australian fashion magazine to let me write a regular column about science and technology. I believe I’m the only journalist in the world who’s published about big bang cosmology and molecular evolution opposite adverts for eye-liner and articles about the latest trends in skirt length.[iii]

I kept this up for 10 years, eventually migrating to Australian Vogue, and I can attest that it’s harder to write about science for Vogue than it is to write for the New York Times Science Section or New Scientist, which I’ve also done.

Why did I want to write for Vogue?

Because women are 51% of the population, and yet the vast majority of people who read science magazines and forums are men – specifically, well-off, well-educated, white men. This has always seemed pretty self-evident to me based on looking at readers’ letters and comments in almost every science magazine. You can see here for a recent (sobering) discussion about this issue on the website of the Topos Institute (Nov. 2022).[iv] I hasten to add that many of my dearest friends are well-off, well-educated, white men, and this is no judgement on them. My point is about the rest of humanity.

Who reads science?

In 2003 after I moved to the US, I researched this topic thoroughly with respect to American science magazines, and the statistics were even worse than I’d intuited. In a nutshell: for the 8 top-selling US science magazines at the time, roughly three quarters of the audience were men. Most were in the upper socioeconomic brackets, and (surprising to me) most were over 35, or even 40.

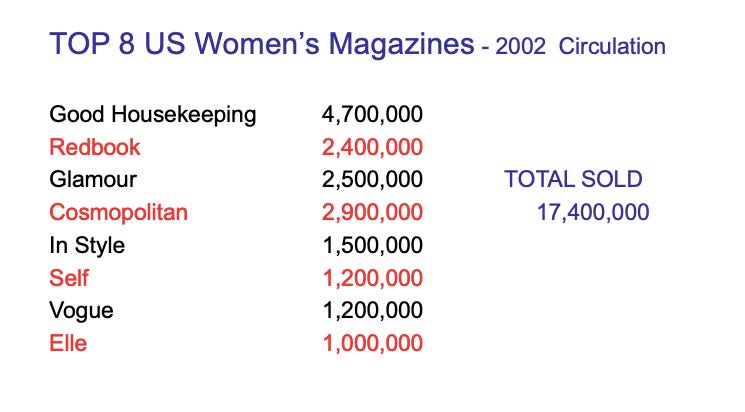

The top-8 science magazines at the time collectively sold roughly 4.4 million copies a month. Compare that to the top-8 US women’s magazines, whose monthly total was 17.4 million. Good Housekeeping alone (at 4.7 million) sold more each month than all the science magazines combined.

So, if I wanted to reach women about science it seemed to me a fantasy to imagine that one day we’d wake up and they’d all have subscriptions to Scientific American or Discover. If I wanted to reach women, I needed to write where the women were – and that meant women’s magazines! To this day, after publishing seven books, including three about the history of physics, I can say that this is the most challenging writing I’ve ever done.

With one exception: In 1989/1990, I conceived and wrote a television science series aimed at teenage girls for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, called Catalyst, which won awards around the world. If you really want a challenge as a science communicator, try explaining the force of gravity or the moire effect to a 14-year-old girl. Try not to bore her stupid in the first sentence.

On Stephen Hawking and writing about physics for my friends

In 1991, I moved from Sydney to Los Angeles and decided to write a book about contemporary physics. Did the world really need another tome about physics? There was already Stephen Hawking’s smash-hit, A Brief History of Time, which remains one of the best-selling science books ever.

Apparently the world did need something else. At dinner parties, once people found out I was a science writer, a version of the following conversation would ensue: “I bought A Brief History of Time,” they would say. “And I couldn’t get past Chapter 1. Can you recommend a book about physics I can actually understand?”

I couldn’t. I speak as someone who admires Hawking immensely. I was one of the few journalists to interview him and write a feature about him before his book came out, while he was writing it. My essay focused on the physics of time, a subject I’ve been obsessed with my whole life, and I spent a thrilling afternoon discussing this with him in his office at Cambridge University. My essay was published in that women’s magazine in early 1987.[v] His book came out in April 1988

A Brief History of Time is admirable in many ways, not the least of which is its brevity. It’s not much more than 100 pages. Why can’t more physics writers emulate that? But its inaccessibility is legendary – even Hawking has joked about this. Could I do better, I wondered. Could I explain theoretical physics to my friends, most of whom are some species of artist? At least I had to try.

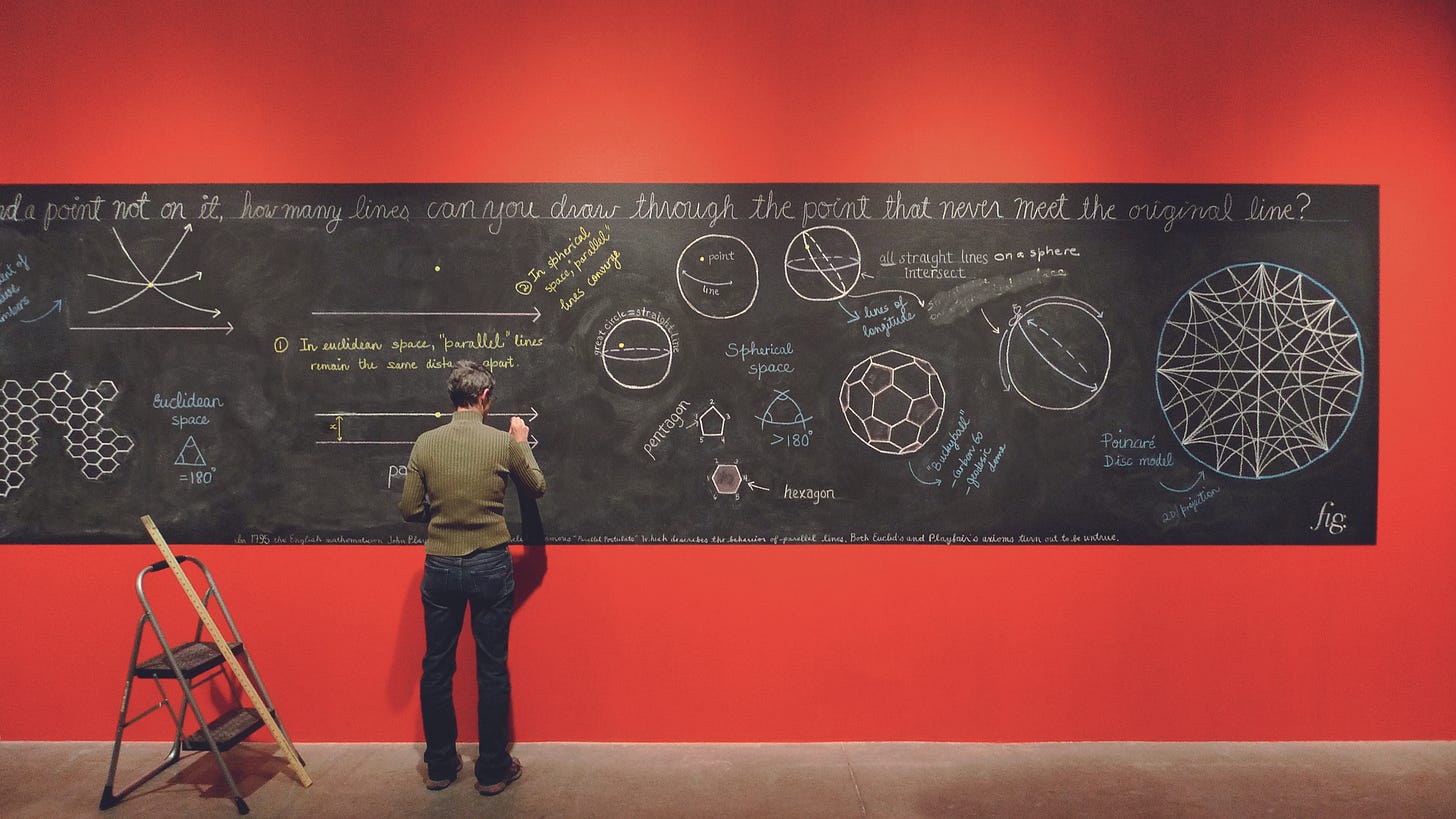

How could one explain general relativity and particle physics to novelists and film-makers and painters? The more I pondered, the more I realized that as science writers we are trained to focus on the answers science discovers. But answers only make sense in the context of questions. If you don’t understand the questions being asked – and why anyone bothers asking them – it’s hard, if not impossible, to appreciate the results.

If I wanted to explain physics to my friends, I reasoned, I’d need to explain what were the specific questions physicists asked and what were the socio-cultural conditions precipitating them to ask such questions at all?

For example: Why does it matter if the sun goes around the Earth or the Earth goes around the sun? I recall in primary school encountering this question (maybe in grade 6), and being dumb-founded by the answer my teacher gave. As he described it, Copernicus replaced a circular system having blue dot at the center, with a circular system having a yellow dot at the center. “So what,” I thought?

“So what?” is the conundrum I set out to address when I started my first book, which I planned as an accessible introduction to physics with a bit of historical context thrown in to describe how physicists’ questions had came into being.

Four years later, when I’d read my way through the equivalent of a masters’ degree in the history of physics (and had my own mind exploded), I had an answer to the “so what” of the Copernican and Newtonian world pictures. What’s at stake here was a fundamental shift in how European humans came to see themselves in a wider cosmological scheme. We went from viewing ourselves as the center of an angel-filled cosmos with everything connected to God – participants in a ‘Great Chain of Being’ – to seeing ourselves as inhabitants of a large rock hurtling through space in a potentially infinite void.

The ‘scientific revolution’ wasn’t just about data and theories, it constituted a massive rupture in thinking about what it means to be human, and what we imagine ‘reality’ to be.

I want to stress the word ‘imagine’ here, because so much science writing – too much science writing – represents science, especially physics, as a search for Truth. Physics is a kind or truth. If physics didn’t represent something about reality we wouldn’t have microchips or lasers. There’d be no laptops or cell-phones, no GPS. The GPS available on your phone right now is so accurate because the satellites conveying the signals are taking into account tiny deviations in the curvature of spacetime caused by the Earth, calculations relying on the equations of general relativity.

The project of quantification

Physics is a wondrous kind of truth that I’ve devoted a large part of my life to describing. It’s also a very partial kind of truth. Physics is the science which aims to describe the quantifiable aspects of the physical world. This is a term I take from the 17th century pioneers. By ‘quantification’ they meant the task of assigning numbers to qualities of the world – things like length, breadth, height, velocity, acceleration, mass, and force.

Lots of things can be quantified, and one way to understand the history of modern physics is as an ever-expanding project about what we can fruitfully assign numbers to. Today we can assign numbers to the curving of space and qualities of subatomic particles – things unimaginable in the 17th century. All of my books have been in one way or another about this project of quantification and the ways in which it has evolved over the last 2,500 years.

For the science we now call ‘physics’ dates back to the ancient Greek philosopher/mathematician Pythagoras of Samos, who first imagined that math could describe the world. As a writer I want to share the achievements of the Pythagorean enterprise with readers of all stripes.[vi]

Yet not everything can be quantified, and numbers aren’t a good descriptive mode for all pheneomena. This is a subject I’ll be coming back to repeatedly in this Substack: What can be quantified, and how? What can’t be quantified, and why?

We live at a time when the project of quantification is being extended far beyond the dreams of Descartes and Galileo in both exciting and troubling ways. On the exciting side, physicists are discovering fantastical ‘topological’ properties of matter, enabling the development of radical new kinds of materials. Matter turns out to be far more enchanted than the Greeks imagined, not mere lumpen ‘stuff.’ One of the more wonderful features of physics today is how it is revealing a much richer, more complex, dynamic picture of our world than science has hitherto described.

On the troubling side, Google and Meta and other tech companies are now in the business of quantifying our shopping habits and behavioral patterns. This is not the same as quantifying motion and mass or space and time. How is this kind of ‘big-data’ science different to physics? What is at stake? Again, the questions matter as much as the answers. I’ll be taking up some of these issues in later posts about data analytics, interacting with chat-bots, the dream of Artificial Intelligence, and consciousness studies.

A promise to my readers

In this Substack I want to engage with science, particularly mathematically inflected sciences such as physics and computer science, as systems with meaning for our lives. At times this will take the form of describing the sheer beauty of answers, for instance, the elegant mathematics uniting quantum mechanics and holography, or the concept of a fractional dimension.

At other times I’ll be challenging claims and rhetoric promulgated by certain strands of science-boosterism and tech utopianism. For it is my belief that if we truly want to promote science, we must be willing to critique its practitioners when they overreach, veer into arrogance, or seem disconnected from the rest of us as human beings.

At all times, my goal will be to make science accessible to as many people as possible, and hopefully to give readers a pleasurable experience. Because few things are so satisfying as being shown how you can understand ideas you’ve been told are beyond you. And too many people have been told that math, physics, and computing are beyond them.

Two promises I make: #1 – I’ll try hard to never underestimate readers’ capacity for creative understanding. In my experience many people are hungering for engagement with math and science if only the ideas can be presented in enjoyable ways.

#2 – I’ll never write more than 3000 words, and rarely more than 2000. Sometimes posts will be very brief; for in this respect Hawking got it right, and we should always bear in mind Mark Twain’s bracing remark: “I would have written a shorter letter, but I didn’t have time.”

Spreading Substack Love

Time is our most precious resource as we lead ever-busier lives with ever-more things to do and read. Writing is everywhere, and there are so many other Substacks. So I’ll end with some recommendations: For the interface between math and computing, Silicon Reckoner by Michael Harris. For great writing about religion and the intersection of tech with transcendental yearnings, The Burning Shore by Erik Davis. For things robotic, Robots For The Rest Of Us by David Berreby. For artificial intelligence, AI Weirdness by Janelle Shane (now on her own website). For wonderments, WonderCabinet by Lawrence Weschler; philosophical musings, Justin E.H. Smith’s Hinternet; environmental insight, Sustain What by Andrew Revkin. Finally, I recommend Aeon and Quanta, two online magazines with lots of great science writing.

A note about subscriptions: All posts on Science Goddess are free. If you feel moved to be a paid subscriber you have my gratitude – it sure helps make this a more viable enterprise.

[Post Length: Approx. 2400 words]

End Notes:

[i] From the famous opening line of “Pride and Prejudice” which is much loved and paraphrased in the humanities.

[ii] Here’s a piece I wrote for Aeon magazine about my decision to leave academia. https://aeon.co/essays/why-is-scientific-sexism-so-intractably-resistant-to-reform

[iii] You can see some examples of this work here: https://www.margaretwertheim.com/science-women

[iv] Anyone who doubts the essence of this claim may like to read this post from November 2022 on the website of the excellent Topos Institute about how, when they posted a video on YouTube explaining the mathematical field of category theory, their own metrics revealed that 0% of viewers were women. They were rightfully troubled and asked YouTube for its breakdown of their general viewership. According to YouTube, the average female viewership of Topos videos was 17.8%. A lot better than 0% but very much in line with what my own research revealed about science magazine readers 20 years ago. It may be that YouTube analytics aren’t wholly reliable, and certainly YouTube appears to promote math videos far more often to males than to females (blame the algorithms). Yet the general picture meshes exactly with my own research. More alarmingly, it’s in line withgender statistics for math and computing college students, who still skew overwhelmingly male. Indeed, the percentage of women students in computer science today is less than when I was a CS student in the early 1980’s. https://topos.site/blog/2022/11/who-is-category-theory-for/

[v] My essay appeared in the Australian women’s magazine “Follow Me”. See here for a pdf of the piece. INSERT LINK

[vi] My first book Pythagoras Trousers is a history of the Pythagorean impulse in physics which explores the idea that the universe can be described by a set of mathematical harmonies, what Hawking and later physicists have referred to as equations in “the mind of God.” https://www.margaretwertheim.com/pythagoras-trousers