Since the white smoke fluttered over the Vatican and a new pope was announced I’ve been thinking about my own experience with the papacy. Above is a photo of me with not one, but two popes: John Paul II, in white, and, lurking in the background, the then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger who’d later be crowned Pope Benedict XVI. The year is 1997, when papal “selfies” were taken by an official Vatican photographer.

The image came about as an unexpected consequence of interests I’d been told were worlds apart – and which many people feel should remain separate. I speak of the domains of science and religion.

The immediate background to the picture is that I’d been invited by the Vatican Astronomer, Father George Coyne, to attend a conference on science and religion at the Vatican Observatory in the papal summer palace outside Rome. In 1997 this conjunction had yet to be seen as cool.

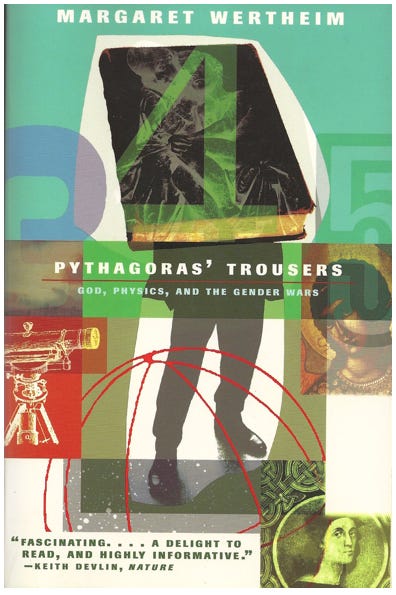

About 20 people were in attendance: some theologians and Jesuit astronomers and academic scholars. My then-husband and I were included because we were making a documentary for PBS in the wake of a book I’d written which charted the 2,500-year-long entanglement between physics and religion – Pythagoras Trousers. After the conference, Father Coyne had arranged for our group to have a private meeting with the pontiff, who was himself interested in science.

At the time in the US, science and religion were widely cast as mortal antagonists, but the John Templeton Foundation had initiated a program to try and change that perception. The foundation was funding, and later hosting, gatherings of scientists and theologians to bridge the perceived divides, and they had agreed to fund a documentary film I proposed.

In the hermetic world of ‘science and religion’, I was one of the very few women – and all the more welcome for it.

I was especially welcome because I had written a book – much to my own surprise – showing how the science of physics had deep religious underpinnings. The fact that Stephen Hawking became so famous for equating a “final theory” with “the mind of God”, was, I showed, part and parcel of a millennia-long history tracking back to Pythagoras, the man who dreamed the dream that became modern physics, and who also believed that numbers were gods. My book traced the threads of deistic thinking in physical science from Pythagoras to Hawking with stops along the way at Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and that great Christian fanatic Issac Newton. It further drew connections between the late-twentieth century quest for a “theory of everything” and mono-theism.

Moreover, the book wasn’t aimed at an academic audience but at general readers. In the world of science and religion studies this was seen as a positive step and so I found myself on the receiving end of quite a few invites to Templeton events. I stress again this was well before the science+religion nexus became cool and every physicist and his dog began to jump on that bandwagon.

Even before we got to the Vatican, our little conference group was privileged to witness a side of the Roman Catholic Church few people get to see. The papal summer palace where the event was held – known formally as the Apostolic Palace of Castel Gandolfo – is perhaps the most extraordinary complex I’ve ever visited. Built on the site of a former Roman palace made by the Emperor Domitian, it boasts a manicured garden like something out of Alice in Wonderland complete with geometric hedges and a checkerboard thingy. At the time, NHK, the Japanese television station, owned exclusive filming rights to the garden so we weren’t allowed to shoot in there. Instead we interviewed Father Coyne in a chicken coop nearby, on whose rovinated walls one could still glimpse fragments of 17th century frescoes – the modern palace having been built in that century for Pope Urban VIII. Urban, of course, is the one who tried Galileo so it’s no small irony that his palace became the site of the Vatican’s Observatory.

Within the garden is also a vast intact Roman horse stable set beneath a hill so the temperature remains constant year-round, and built, we were told, by Nero. Its gracious vaulted ceiling and cool fresh air were an enduring testimony to Roman architecture.

The Castel itself is situated on the rim of an extinct volcano and from out the windows one could gaze down into the azure pool of Lake Albano, a view sufficient to hint at something divine. To live here for the summer – away from the grit and noise and heat of Rome – would surely enhance one’s sense of tranquility, and power. It was a perfect place to be discoursing on ‘higher’ things.

*

After the beauty of Castel Gandolfo, I doubted the Church could offer anything more amazing. I was wrong. For our meeting with the pope we were instructed to gather at the back wall of the Sistine Chapel at an allotted time. My husband and I spent the prior morning touring the Vatican Museums, and even as someone who’d grown up Catholic with a pretty good sense of the Church’s history of global plundering, I found myself overwhelmed by the sheer amount of Stuff. That was nothing however compared to what was awaiting Backstage.

On the appointed hour a door opened in the rear of the Sistine and a wizened cleric met us, along with Father Coyne, to escort us to the pontiff. It turned out we needed a guide because it was a good 30-40 minute walk to our assigned meeting room. If the public side of the Vatican is opulent, it’s only a fraction of what’s to be seen on the private side.

Mile-upon-mile of polished marble columns and inlaid floors. More gilt, frescoes, and paintings than I would have though possible in one place. But what impressed me most, was the frocks! Gore Vidal has called the Catholic Church “the greatest fashion show on Earth” – he’s not wrong.

There were cardinals swathed in red satin. Bishops in white satin. The Swiss Guards in their red, blue, and yellow silk-and-velvet pantaloons. All of it immaculate. Not a crease or stain in sight. Even the common priests seemed pressed and preened.

As we walked past hundreds of be-robed prelates a question started to niggle in my mind. Who was doing all the laundry? This massive yardage of silk and satin and snowy white lace; someone had to be washing it, starching it, ironing it? Who might that be? I thought it would be rude to inquire. But eventually – as one of the few women in the building (it seemed) – I couldn’t bear not knowing. So I sidled up to the question with Father Coyne. A down-to-earth man from a large working-class Irish-American family in Baltimore, Coyne (a Jesuit) had a great sense of humor and strong sense of social justice. He wasn’t in the least offended. Oh, he answered brightly, there’s a fleet of old ladies all over Rome who do the washing. It’s their service to the Church.

That’d be right, I thought: the men get to wear the finery, the women get to clean it!

By the time we got to the pope, even the theologians in our party were visibly a bit uneasy with the sheer opulence of everything. Many of them were protestants, so I suppose they already had a sense of impropriety about such lavish displays.

I thought about my long-departed grandmother, a lower-working-class Irish-Australian Catholic and herself the mother of a priest (my uncle). What would she have made of all this? On the one hand, I wish she’d lived long enough to know her granddaughter had met the pope. She’d have felt so proud. But as someone who scrimped by her whole life and worked so hard, I can’t imagine she’d approve of this much flash.

Then again, had she lived in Rome, as a devout Catholic lady she might have been volunteering to do some of the washing. I wonder?

In any case, by the time we got to the pope I felt ashamed of my natal religion, sick to my stomach, binged-out on eye candy, assaulted by the soul-less parade of wealth.

*

Some people claim Princess Diana, in her life, shook hands with more people than anyone else. But I’m certain she’s beaten hands-down at this by whoever is pope. As we walked into our meeting room with John Paul, a door into an adjoining room briefly opened and closed and there we could see he’d just been meeting with another group, of priests. I’m not sure how often, but on appointed days he goes from room to room meeting one group after another – and (Father Coyne told us) shaking hands with every person in every group!

For us, he gave a short talk about the value of science to faith, and of faith to science, then we lined up to shake his hand. An official Vatican photographer was there to capture the moment in perfect framing, and for a small fee we could order a copy. Which of course I did.

What none of us could have known at the time was that we were, ultimately, in the presence of two popes. Standing by John Paul II, and captured in my photo, was Cardinal Joseph Alois Ratzinger, an ultra-conservative Bavarian cleric who in 2005, after John Paul passed away, would be named pontiff himself.

*

It had not been my intention to write a book about physics and religion. When I began the book that became Pythagoras’ Trousers, I only wanted to produce something accessible about physics, to explain to my friends – many of whom are arty types – why I love the subject so much. Ever since I was a child I’ve been obsessed with the questions of how and why mathematical relationships exist in the physical world. I went to university to study physics because I needed to get insight into these issues for myself. On the how front, I learned a lot. But on the why front, I learned nothing. So after university, when I had decided not to pursue physics grad-school, I set myself the task of learning about the history of the field.

What I learned astounded me: I found that in every era of Western science, physicists and their precursors had been engaging with religious issues. Stephen Hawking’s phase about “the mind of God” wasn’t an anomaly, it was the tail-end of thousands of years of Greek and Christian deistic-scientific thinking. And so a book intended purely as an exercise in science communication became a take on the history of science. It was published in 1995, and I’m proud to say is one of the earliest non-academic books to deal with science and religion – a topic that later took the publishing world by storm.

I had no idea when I began it that I’d end up writing about god. Nor that it would lead me to shake hands with a pope. If the lord moves in mysterious ways, science does too.

******************

Correction: an earlier draft of this Substack stated the year I met the popes as 1987. It was 1997. You all will excuse the brain fog, as I’m caring for my mum who has cancer.

******************

Endnotes:

Though the documentary we made did air on PBS, it did not turn out well; for the reason that PBS insisted my husband (Cameron Allen) and I work with a producer they had experience with. He and his anointed co-producer were far more socially and politically conservative than me and we disagreed on pretty much everything, so the program ended up bland and anodyne, not the alive, open-ended exploration I had envisioned. It remains a source of sadness to me that I was out-gunned on this, and that too much of what we continue to hear about ‘science and religion’ today is either insipid or a lie.

I haven’t been a Catholic since my parents left the church when I was seven, but I am very grateful for the upbringing my mother Barbara Wertheim gave me, rooted in a strong sense of social justice derived from her own working-class Irish-Australian Catholicism.

It does science an immense disservice to pretend that ‘faith’ and ‘reason’ are polarities between which people must choose. The greatest ‘faith’ I’ve encountered in my life is the one animating modern physics: that there is mathematical description for All that Is.

In 2016 the main structure of the papal summer palace was opened to the public as a museum. So you can go see it for yourself. I’m not sure about the gardens.

Margaret, Oh, I'm dying with envy. What a great story! And what a great question to ask as your tour the Vatican: Who does all the laundry? Thanks for this reminiscence.